Breed standards exposed

If you haven’t seen the 2008 British documentary “Pedigree Dogs Exposed,” whether you’re a horse breeder, a dog breeder or just an animal lover in general, you should watch it. It makes clear that the entire concept of dog breeds and breed standards is flawed.

Within each breed, standards are set by people with a variety of hidden agendas and lack of knowledge, and, as you will see in the documentary, many of the standards contradict good health, in some cases promoting a breed type that causes the animal pain and early death. The footage of the top German shepherds from the show world is just appalling. Those poor dogs have been bred to some ridiculous breed standard that is making their back legs look like silly puddy, and there in the documentary stands some pompous judge praising them as perfect when the rest of us can see that the dogs can’t walk at all.

And just about the time viewers recover from that segment, the documentary moves on to talk about Rhodesian Ridgeback puppies being euthanized if they don’t have a ridge on their back, with these killings being recommended by their breed society. The ridge actually is a genetic deformity with health consequences, the documentary explains. The breed society is killing the healthy dogs, all because someone has foolishly written a breed standard that says the ridge needs to be there.

I suspect this type of close-mindedness is happening in every breed organization to one extent or another.

The BBC interviews a number of veterinarians, including the chief vet of the RSPCA, and college professors from the United States and Britain, who all decry what’s happening to dogs. You easily can see how their comments apply to horse breeding, as well.

Since the mid-2000s, I have been railing against the Connemara society in America for following its Irish counterpart in weeding out the more refined Connemaras. Both groups are doing this by instituting inspections that will fail a horse for not being the right type (defined as an animal with heavier bone), even if the refined horses have excellent conformation and wonderful temperaments.

My one-woman movement started in 2005 after an inspector failed a wonderful young Connemara stallion and then felt the need to share with me her reasoning. The owners of this horse, relatively new breeders, were crushed, and this inspection failure lessened their faith in their horse as a stallion. If he wasn’t going to be accepted, then did they want to pursue using him as a stallion? I didn’t follow up on where the horse landed, but it was heartbreaking to see them lose faith in him and to see him denied a breeding career that otherwise might have turned out very successfully.

Meanwhile, the inspector who failed the horse e-mailed me that:

1) This stallion was nice by anyone’s standards and was black and sleek, reminding her of my stallion, but the inspected pony was not the right type and therefore not approved; she thought it was a grandson or great-grandson of my stallion (it was not, though that did not diminish my anger).

2) All black, sleek, fancy-looking ponies remind her of my stallion.

3) My stallion does not “fit the standard.”

Perhaps it’s relevant to point out that our stallion used to finish higher in conformation than her stallions on a regular basis when judged by open hunter/jumper judges in the late 70s and early 80s. This is when Connemara board members, including this inspector, started coming up with new breed standards and requiring that judges of Connemara classes be familiar with those new breed standards. I remember my dad coming home from one meeting and describing the new standards as the perfect description for a Dachshund. Short legs and long backs were both included as part of “good” conformation.

We chose to ignore the whole inspection movement until 2005, when I realized other horses were being wronged by this inspector’s hatred for my stallion and other refined horses.

After watching this BBC documentary, I see that, in my anger, I wasn’t seeing the forest for the trees.

The MUCH larger question is: Should we intentionally have specific breeds at all, much less breed standards?

Scientifically, the argument would seem against it. Inbreeding among all breeds is rampant, allowing flaws to spread quickly and other genetic problems to crop up. As a British geneticist puts it in the documentary: This type of breeding would be highly illegal in humans.

Then one has to ask: Should there be breed organizations, or are they the root of the problem? Certainly, one could see the need for tracking the lineage of animals, promoting animals with similar genetic backgrounds and sponsoring events that promote activity of those animals. All good.

But to encourage any group to continue breeding within the same genetic pool and not encouraging those breeders to incorporate the diverse and wonderful pool of genes elsewhere, strengthening the quality and health of their herd, seems wrong.

In fact, breeding to outside lines is what the Connemara society is trying to “correct.” The Irish let thoroughbred and Arabian bloodlines into the Connemara breed in the 1940s, and since that move added more speed, agility, competitiveness and a bunch of other good traits to this breed, not surprisingly, the horses with thoroughbred backgrounds in particular were VERY popular, making people with other bloodlines pretty darn mad. This is their payback. Rather than embracing the better horses, they’re going to bury them.

Below, I’ve typed out the text of the BBC documentary through the first 23 minutes or so.

The most telling quote in the whole thing is this one:

RSCPA chief veterinarian Mark Evans: “When I watch Crufts (Britain’s top dog show), what I see in front of me is a parade of mutants. It’s some freakish, garish beauty pageant that has nothing frankly to do with health and welfare. The show world is about an obsession about beauty, and there is a ridiculous concept that that is how we should judge dogs. Best in breed means you happen to be closest to this thing that’s been written on a piece of paper, is what you should look like, takes no account of your temperament, your fitness for purposes of potentially as a pet animal, and that to me just makes absolutely no sense at all.”

It loses something in print, because he talks in phrases. But note his disdain for people who play god by writing down breed traits on a piece of paper and then forcing people to breed to those standards.

This documentary caused a huge uproar in Britain. In fact, the BBC stopped showing the Crufts dog show on its network after doing so for 40 years; two majors charities withdrew their support; and Pedigree dropped its sponsorship of the show. As a result, the Kennel Club asked for an independent investigation into dog breeding practices, and that report was released Jan. 14, 2010.

The report includes criticism of some breeds encouraging extreme characteristics — such as smaller heads, flatter faces and more folds in the skin — leading to health problems. The heavy bone requirement now required of Connemaras seems to fall into that “extreme” category to me.

The compelling thing in watching the documentary is how sure these breeders are that they are doing the right thing, even as the rest of us watch with our jaws dropped. I don’t know what it will take to change the mindset of these dog breeders, but change they must. The world needs to take a hard look at what it’s doing.

So, here is the text of the BBC documentary, which picks up a few minutes into it after the introductory footage showing several gravely ill animals, with defects caused by breeding and in-breeding to set standards:

—–

British geneticist Steve Jones: “People are carrying out breeding which would would be first of all highly illegal in humans and second of all absolutely insane from the point of view of the health of the animal.”

RSCPA chief vet Mark Evans: “The cause is very simple. It is competitive dog showing. That is what is causing the problem.”

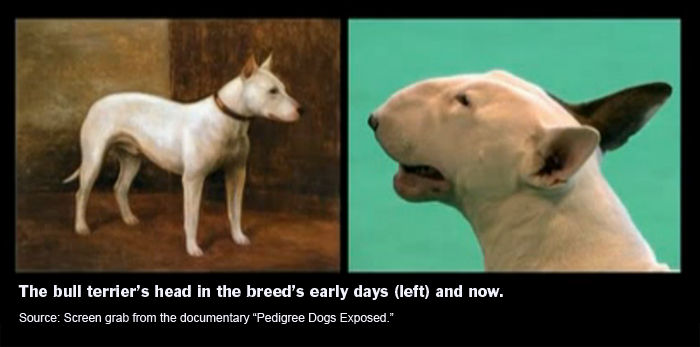

Narrator: “Look at what 100 years of the show ring has done to the Dachshund. Today’s dogs have much shorter legs. The original bull terrier on the left had a normal shaped head, markedly different from today’s dog on the right. This is how the change looks from the inside (illustration of deformed skull).

“And then there’s the German shepherd, the subject of fierce debate, and that’s because they used to look like this (photo of police-type German shepherd). In fact, working German shepherds still used by many police forces do still look very like the original dogs, but the show dogs have become more and more extreme, and it’s had a major impact on the way they move.

“We asked a top orthopedic vet to look at the footage of German shepherds we recorded at a top championship show.”

Orthopedic surgeon Graham Oliver: “He’s got what we call an ataxic gait. He doesn’t have full coordination or control. His hocks are wobbling from side to side, and if he had strength and coordination in his hind limbs they would be much more solid than that. Of those dogs overall, I’d say the majority of them are not normal.”

Narrator: “We see much the same at Crufts two months later. Critics now refer to the show German shepherd as half-dog, half-frog. Even the famous German dog that wins best of breed seems to sag on his back end.

“But Crufts judge Terry Hannan insists that it is the show dog, not the working dog, that is the correct version of the breed.”

Crufts judge Terry Hannan: “The old fashioned UK type of dog, or the working dog, you would never see them in a show ring because anatomically they are not correct.”

Narrator: “Because you believe that the shape that is going around the show ring is the dog that is better structured to do the job it was bred to do.”

Crufts judge Terry Hannan: “It’s more to the breed standard.”

Narrator: “And that’s the whole point of showing. To produce a dog that most closely resembles the blueprint laid down in the dog breeders’ bible: the Kennel Club breed standard. The breed standards are a set of rules that lay down what a pedigree dog breed should look like. The size, shape and color of every recognized breed.”

Beverley Cuddy, editor of Dogs Today: “The predictability of pedigrees is what makes them attractive. You can guarantee the height, approximately the temperament and lots of other things. But unfortunately you can also guarantee what might go wrong with them.”

Narrator: “Every single breed has its own health problems, some minor, some not.

“Labradors are plagued with joint and eye problems. Springer spaniels are affected by an enzyme deficiency found only in springer spaniels. Golden retrievers suffer a high incidence of cancer. And the West Highland white terrier, the Westy, is beset by allergies.”

Beverley Cuddy, editor of Dogs Today: “The dogs are falling apart, and the number of genetic problems are increasing at a frightening pace.”

Narrator: “There are 500 known genetic diseases in dogs.

“Boxers suffer from several life threatening health issues, including heart disease and a very high incidence of cancer, especially brain tumors. In common with many other breeds, they can also suffer from epilepsy, and behind closed doors, hundreds of owners are struggling to cope with this most distressing of conditions. Zack here is just 2 years old.”

[Demonstration of epileptic seizure.]

Professor James Serpell of the University of Pennsylvania: “You know, nobody bought into that idea (of seizures) when they took that puppy home. And it can be devastating, really devastating, because people love these animals. You know, it’s like seeing a close relative falling apart.”

Narrator: “There are no official figures to say how many boxers suffer from epilepsy, but in some breeds, it is 20 times the rate found in humans.

“Today’s dogs have been molded by man into almost every possible shape and size, from dogs as small as kittens to giant great danes. But dogs originally looked like this, their ancestor, the wolf.

“But dogs were not always such victims of fashion. Early dog breeding mimicked the natural selection that makes the wolf so exquisitely home to its environment.”

Professor James Serpell of the University of Pennsylvania: “Dogs were essentially bred for function. So they served practical functions, be it hunting or guarding, or whatever it was. And those dogs that did the job well were then bred to other dogs that did the job well, and through that process you got the evolution of modern breeds. But, come the middle of the nineteenth century, all of that changed.”

Narrator: “The new Victorian middle class had time and money on their hands. Dogs became a status symbol and dog breeding a sport.”

Professor James Serpell: “They got the idea that they could produce perfect specimens of these different dog breeds that were around at that time. They also got into creating new dog breeds and then perfecting them. And the whole focus changed from being concerned with the function of the breed, what it traditionally was used for, to its appearance, its physical appearance.”

Narrator: “And where better to show off your skill at playing god with dogs than at a dog show. The first one was held in the 1850s, and they quickly became wildly popular. So popular that they soon needed an organization to run them. Enter, in 1873, the Kennel Club. One hundred and thirty-five years later, the Kennel Club is widely accepted as the guardian of pedigree dogs, and it has impeccable establishment credentials. The Kennel Club’s patron is her majesty, the queen, herself a breeder of pedigree dogs. Today’s Kennel Club is involved in all kinds of canine activities, from agility competitions to obedience training to funding scientific research into dogs by its charitable trust, but at its heart the Kennel Club has two main roles: First, it is a registry which records the lineage of purebred dogs. When you buy a Kennel Club registered puppy, it will come with a pedigree certificate like this one showing the pups’ parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on. And it regulates most dogs shows in the UK, including most famously Crufts. Many of us watch Crufts on the BBC every year, but not everyone sees it as a celebration.”

RSCPA chief vet Mark Evans: “When I watch Crufts, what I see in front of me is a parade of mutants. It’s some freakish, garish beauty pageant that has nothing frankly to do with health and welfare. The show world is about an obsession about beauty, and there is a ridiculous concept that that is how we should judge dogs. Best in breed means you happen to be closest to this thing that’s been written on a piece of paper, is what you should look like, takes no account of your temperament, your fitness for purposes of potentially as a pet animal, and that to me just makes absolutely no sense at all.”

Narrator: “But behind the glitz and glamour of Crufts. behind the doors of the Kennel Club’s $20-million pound HQ in London’s posh Mayfair, lies a dark and dirty secret. The Kennel Club was born out of the eugenics movement. The idea that we could improve the human race by controlling who bred to whom. It sounds incredible now, but the eugenics movement was hugely popular. Eugenicist doctrine taught that the genetic improvement of man lay in breeding only best to best in purifying the humane race of undesirable traits and in never allowing any mixing between races. The problem was that what was considered best was often decided solely on what you looked like and very often on what race you were. And then, in the 1930s, the eugenics movement found its ultimate champion.”

Quote by Prof. Steve Jones about Adolph Hitler.

Narrator: “The Holocaust exposed eugenics as morally flawed. Its ideas about purity make no scientific sense, either. And yet one organization almost unnoticed has continued to embrace eugenicist principles.”

Professor James Serpell: “That view is very much still propagated by the Kennel Club today. It’s all about maintaining these lines of very pure, very unsullied aristocratic breeds.”

Narrator: “It’s not just that they don’t allow any mixing. True to the Kennel Club’s eugenicist principles, breeders sometimes discard dogs born that deviate from the breed standard.

“The ridge on a Rhodesian Ridgeback serves no useful purpose. In fact, it’s been known for decades that the ridge is a mild form of spinabifida that can cause serious health problems. But the ridge is enshrined in the Kennel Club’s breed standard as the defining feature of the breed, so every Ridgeback must have one. The problem is that about one in 20 ridgebacks is born without a ridge.”

Ann Woodrow, Rodesian Ridgeback breeder: “And we do have trouble nowadays with the young vets who tend to see everything in black and white who won’t put them down. (They say), ‘It’s a healthy, beautiful puppy. There’s nothing wrong with it except it hasn’t a ridge.’ And you say, ‘Well, actually, they’re meant to have ridges.’ It’s not easy. And usually we end up having to go to an old vet that we’ve known for years to just quietly put them to sleep. I would rather they be put down in my care than they land in the hands of the fighting people, which is appalling.”

Narrator: Neutering them instead is also permitted, but it’s still enshrined in the Rhodesian Ridgeback Club’s code of ethics that ridgeless puppies shall be culled.”

RSCPA chief vet Mark Evans: “It’s morally and ethically absolutely wrong to cull perfectly healthy animals simply because of the way they look. The concept for instance in Rhodesian Ridgebacks of actually saying we’re going to deliberately breed them and only harvest the ones that have the ridge, which is a deformity anyway, and the ones that are the healthy ones are the ones we kill, that is disgraceful.”

Narrator asking a question to the chairman of the Kennel Club: “Should healthy puppies be culled on purely cosmetic grounds?”

Ronnie Irving, chairman of the Kennel Club: “No, should healthy puppies be culled? Absolutely not. There is no reason in my view to cull puppies on cosmetic grounds, absolutely not, and I wouldn’t want the Kennel Club to be associated with such an idea.”

Narrator: “But Ridgebacks are not an isolated example, and the Kennel Club knows this. Culling puppies because they don’t meet the Kennel Club breed standard is not perhaps as common as it used to be, but it still happens. Victims include great danes born with the wrong markings, white German shepherds and white boxers.”

Narrator to Irving: “Such practice happens all the time.”

Ronnie Irving, chairman of the Kennel Club: “I wasn’t aware of that until you told me that this morning, but I’m appalled by that, and I will do what I can to prevent it, but I’m not sure what I can do to prevent it.”

Narrator: “Well, you could change the breed standard, and there’s a good reason to do this in Rhodesian Ridgebacks. About 10 percent of Rhodesian Ridgebacks suffer from a nasty condition called dermoid sinus. It looks innocent enough. Just a pinprick-sized hole on the surface of the dog’s skin. But these holes often burrow right into the dog’s spinal cord or brain, an open channel through which lethal infection can travel. Dogs born without a ridge don’t suffer from dermoid sinus, so it would make perfect sense to change the breed standard, perfect sense, that is, to anyone other than a Ridgeback breeder.”

Breeder Julie Bates: “No, I do not believe in that. Quite frankly, I think it’s a rubbish. Without the ridge, they’re not a Ridgeback, are they? It doesn’t matter, it may have a beautiful type, but without the ridge, it isn’t a Ridgeback.”

Breeder Ann Woodrow: “When they found the people in Ridgebacks were using them genuinely in Africa for hunting, they found that the best hunting dogs were the ones with the ridges.”

Narrator: “How many leopards do you have in High Wickham?”

Breeder Ann Woodrow: “Um, not too many. I wish there were a few more. Get rid of the (some animal) that are eating my roses.”

Narrator: “Soon after we raised the issue with the Kennel Club. we discover that the Kennel Club has written to the Rhodesian Ridgeback Club, which then removes its code of ethics from its website.”

… And the documentary goes on from there with Ridgeback breeders complaining that the Kennel Club did approve its breed standards, complete with the puppy culling suggestion.

—–

If you watch the German shepherd and Rhodesian Ridgeback parts of the documentary and still feel that every breed should do what it wants, then you’ve come to the wrong website. If you feel it’s time that sane animal lovers take a stand and come together to force change, not just in any particular breed but throughout the animal kingdom, then please give me some of your ideas or point me in the direction of others who feel the same.

I’ll always fight the good fight for good Connemaras. But, as the BBC documentary clearly shows, breed standards are not just a dog or horse problem. All breed standards are problematic and perhaps the problem even goes beyond that. Should there be breeds where no outside lines are allowed in? Should there be breed societies that make rules that don’t make sense? It all needs to be addressed.