Latest Connemara inspections measure thickness of leg, not quality of horse

I also saw part of the ACPS Connemara show held the previous day (an open schooling show with some Connemara classes). The weather was ridiculously hot for the show day. I applaud anyone who made the trip, and some came from thousands of miles away.

I liked every Connemara I was able to identify at the show in one way or another. There was a big range in looks and colors, reflecting the diverse genetic background of the breed (many breeds meeting on one island). The broad mix was ironic given that there is so little love for the more refined horses now.

Actually, at this inspection, a few mares were more refined than a horse that failed an inspection in the past for being too refined. The pretty horses passed this time. In fact, all but one horse were approved. I concluded that subjectiveness over what is “too refined” is a huge part of this process, and approval is based on the luck of which inspectors you draw.

I videotaped the first two Connemaras being inspected. Both were stallions. That video is here.

Everyone involved knew I was there videotaping, so I’m going to assume that I was shown the best inspection process the ACPS has to offer.

The three inspectors were Sara McCrae Thrasher, Donna Duckworth and Marian McEvily.

Thrasher was the lead inspector.

I had not met her previously, but my overall impression was good. She seems nice and intelligent.

But I fundamentally disagreed with her opening statement that inspections were improving the breed, as well as her assessment that the first two horses had good bone or good “type” (code for rugged, not refined). The two horses did have big bone. I don’t consider big bone to be good or correct Connemara “type.”

The first stallion (14-1 hands) was approved and granted premium status; the second stallion (13-3 hands) was not approved.

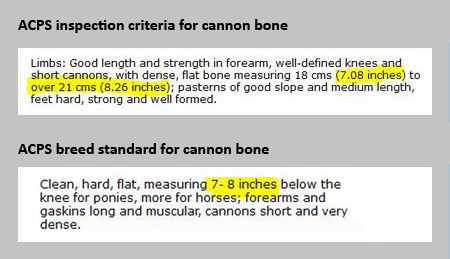

Both had a cannon bone circumference of 9 inches. The inspection criteria requires a cannon bone of 7.08 inches to over 8.26 inches.

The worldwide breed standard for Connemara cannon bone circumference is 7.08 inches to 8.26 inches (or 7 to 8 inches for those who prefer to round), period. There’s no over.

Both stallions should have failed if one is going to have inspections that judge a Connemara against the breed standard. I would throw out inspections and the breed standard and encourage people to breed useful and healthy Connemaras.

I’m trying to get US Equestrian to care that the inspection criteria doesn’t match the breed standard, likely because all the inspectors’ Connemaras have big cannon bones and would fail. So far, crickets from US Equestrian.

The ACPS website from at least 2008 to 2013 had conflicting cannon bone requirements between its inspection criteria and breed standard.

ACPS inspection requirement for cannon bone (top) versus ACPS breed standards requirement (bottom) from at least 2008 to 2013.

I pointed it out on this website, and then the cannon bone breed standard was removed from the ACPS website. But it has not been removed from the websites of other societies around the world, so feel free to look it up. The cannon bone breed standard has been the same since Ireland created it a century ago.

Rather than great bone, I would suggest that the two inspected stallions in St. Louis had exaggerated bone for their size. And that’s fine in and of itself. I could see breeding them to light mares.

But the ACPS has gotten into this mindset that bigger is better, which will result in people continuing to breed even bigger bone, until we’re looking at a cannon bone of 10 inches or 11 inches on a pony (since we’re not allowing the breed to grow taller as humans do). Thasher’s approved stallion advertises a 10-inch bone. He’s just taller than a pony.

I did extensive research on how heavy leg bone affects a horse; bigger is not better; bigger is a hindrance, according to the scientific data.

Horses competing in the 100-mile Tevis cup average much less cannon bone. These are horses that perform under extreme stress.

I am unaware of the ACPS doing any research on how bone circumference affects Connemara movement. The ACPS’ continued emphasis on heaviness will backfire, I predict.

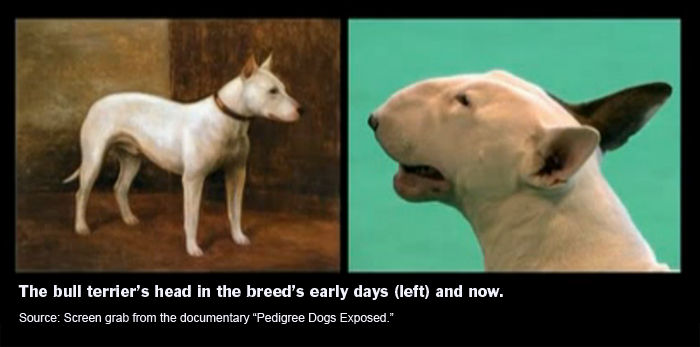

A top veterinary complaint in dog breeding is that breeders have taken breed standards to the extreme, ruining the health of the bull terrier, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and German shepherd, among other popular breeds. Look at this screen grab from the BBC documentary “Pedigree Dogs Exposed.” The image on the left is an early bull terrier, and the image on the right is the dog now, as breeders have tried to outdo each other on an exaggerated head.

A fifth of all bull terriers are deaf. Anyone want to bet that the extreme head shape isn’t involved? I wouldn’t.

Thus, I greatly disagree that inspections and exaggerated cannon bone circumference are improving the breed.

Some of the inspected horses were very sticky in their movement (the horses didn’t readily go forward when asked), and I wondered if they would be useful or interested in being ridden. I will never know. No one rode the horses during the inspections. I’m not sure the horses were trained other than to trot in hand.

Some other observations:

1) The American Connemara Pony Society is getting old. I’ve said that before, but it was blatantly obvious at the inspections, as well as the show, particularly during the conformation classes. The Connemaras were mostly handled by adults.

This has not been the case in the past. I grew up in the 1970s, before inspections became the main ACPS activity. I was surrounded by tons of kids riding Connemaras. And when shows were held, children came from many other states.

You will not get more kids involved by making inspections the central focus of the breed society. This process is discriminatory (it says some ponies are not good enough to be approved Connemaras; it’s a form of bullying). It doesn’t dovetail with what millennials care about: diversity, fairness and coming together for the common good. Millennials are not about being judgy and exclusionary.

Also, inspections are really boring.

In fact, one adult at the inspections asked the two kids in attendance if they were bored. I’m no kid, and I was bored sitting and staring at an empty ring most of the time.

In 10 years, the age issue is going to be a huge problem for the ACPS. Ignoring it will not make it go away.

2) The inspections provided little information for onlookers.

The actual inspection of the first two stallions took about 12 minutes each. As you’ll see in the video, the inspectors did some measuring, then asked the horse to move a little. The stallions did a liberty phase of running around loose in the ring, while the mares did not, so the mares’ inspections were shorter.

The inspectors gathered privately for maybe 15 minutes and made a decision. At this inspection site, an apparent new feature was added: The inspectors told the crowd what they thought of the horse and why it was or wasn’t approved.

I appreciated the effort to add the educational phase, but I felt I learned little about each horse’s conformation. If you tell me a horse is base narrow or moves too closely, I have to see the so-called flaw to learn what it is. I was on the rail of the ring but certainly not close enough to see that kind of detail. The horse was gone by the time I heard the critique.

3) The ACPS did not publish the time that the inspections would start so I had to guess. I wondered whether the society wanted onlookers.

I showed up at 8:30 on a very humid Sunday. The inspections got underway at about 9:25 a.m. By 11:30, five (maybe six) horses had been inspected out of 13 total. Air circulation is awful in the indoor ring that was used, and most of that time, I watched the empty ring, so I left at 11:30.

4) The money would be better spent elsewhere.

I figured up the cost of these inspections based on all horses getting their nominations in on time.

The two stallions should have paid inspection fees of $200 per horse ($400 total).

The 11 mares should have paid $100 per horse ($1,100 total).

Hotel rooms in the region run from $50 to $100 a day. Let’s assume the ACPS sprang for the $100 room for each of the three inspectors for three nights ($300 per night for a total $900).

Add in another $180 total for their food for three days ($20 per meal, three meals, three inspectors).

Flying in the inspectors would be another expense. A roundtrip flight from, say, Gainsville, Fla., to St. Louis, Mo., booked a month in advance is roughly $400. For three inspectors, flights might cost a total of $1,200.

By my count, the estimated grand total cost of holding the inspections ($2,280) would be more than the nomination fees ($1,500). Maybe it broke even with some severe penny pinching.

Meanwhile, the owners spent a lot of money on transportation and housing for themselves and their horses, but most got to go home and advertise their horses as approved or premium, though I would argue that the buyer should beware of those labels.

What if all the money put into these inspections were used to do something that actually created premium horses rather than just giving them the label? What if regular clinics were held with expert trainers across the country? What if the ACPS held the equivalent of a learn to skate program or Girl Scout badge program, and kids moved up a ladder of skills by accomplishing goals and earning prizes?

What if the ACPS tried to attract and energize new riders, who will be the future Connemara owners in America?

Wouldn’t that be a better use of these funds?

In 10 years, when the current crop of very longtime Connemara officials, who have run this breed society since the 1970s, are much less ambulatory, perhaps even wheelchair bound, and we’re looking around for Connemara owners, I guess we’ll have our answer.